There has been a great deal of discussion in Bhutan lately on changing the way we teach history in school – including a recommendation to resume teaching it in the national language, Dzongkha. The role of teaching history is not to improve the national language but to instil national pride and identity.

First of all, any debate is better than no debates at all. Although public discussions do not tantamount to much these days, for the sake of my own satisfaction and my duty as a citizen, let me share my views on this very important topic.

For me, the essence of history goes beyond improving the national language or becoming a global citizen. Studying history should instil a sense of national pride and understanding of who we are as people and where we came from as a nation. Then as we read the world history we come together as humanity in mutual solidarity and learning from each other.

And hence, it doesn’t really matter whether it is taught in English or in Dzongkha. It should be taught in a language that best reaches the hearts and minds of the audience. More importantly, it should be taught by people who are passionate about history. There is no doubt that teaching in Dzongkha could provide a rich languaculture experience. But where is the capacity – let alone the passion or the motivation.

In any case, to be frank, the way it is done now, it is serving at nothing. And the fallout could be a declining sense of national pride and loss of the collective identity. Every man will start fending for himself.

I love history. When I was in Sherubtse I used to often sit in history class, which was taught by a superb Indian lecturer by the name of Somaranjan (whom they lost, by the way). I also conducted couple of guest lectures on the European Renaissance and the Advent of Modern Mass Media in Bhutan. I used to also spends long evenings talking with another history lecturer, and my good friend, Sumjay Tshering.

However, I am yet to meet one student who is passionate about the subject. That’s because learning history is reduced to memorising dates, names and places. As Einstein once said, what is the use of remembering something that you can find written somewhere? If I may requalify Mr. Einstein, in this day and age of Lord Google and Prophet Wikipedia, facts and figures are only important to us to the extent that we know where to look for them. Of greater importance should be to understand the question why than the question what.

The way history is taught is fundamentally wrong. The topic is treated as linear and isolated occurrences of events. Worse still, every event is viewed with a telescopic lens focusing on the specific event only. And hence, students of history can provide names of people and places and dates – in a chronological order – more or less.

But history is not linear. It is lateral. It is contextual. It doesn’t take place in isolation. Hence, when we teach or talk history we need to give the broader contexts.

Take for example the Treaty of Punakha 1912. If we look at the Treaty with a lens pointed at that event only, we might feel that we actually got a bad deal. How did we bind ourselves to the British – to advise us on foreign relations?

Now, broaden the horizon of that era. Look at what was happening around Bhutan. The British had been ruling India for over 200 years. They had colonized half of the Earth’s landmass. They had crushed without mercy every attempt of the Indian independence movement. Now shift your eyes towards the north. Again, there, the British had gunned down over 700 Tibetan ‘soldiers’ forcing their way to Lhasa. The Qing Emperor had issued new threats by claiming sovereignty over Nepal and Bhutan. They sent armies to Tibet to crush rebellions. The Great Game was still on. There was every chance that we could have been wiped out. And mind you, history has seen empires and kingdoms far greater than us vanish at the hands of colonial powers.

If we give bigger geopolitical contexts to the Treaty, we then not only understand the event better, we also begin to appreciate our leaders more – in particular the masterstroke of Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck. His foresight, statesmanship and wisdom have kept us safe and independent when all other more prosperous nations from that era disappeared. We feel proud as Bhutanese. We feel grateful. The fact that we even managed to extract a treaty out of the British was an achievement in itself.

Take another example – and another dimension. The founder of Drukyul, Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel, promulgated the Chayig Chenmo (the Great Code of Law) in 1637. However, the year is just a ‘number’ unless we can bring some interesting context to it. What if we said that Chayig Chhenmo was ahead of the much-celebrated American Constitution by a good 150 years? To point out that we were ahead of the Americans? Now isn’t that a factually interesting comparison that would catch the ears of a listener? Wouldn’t our students, and people in general, take more interests in history?

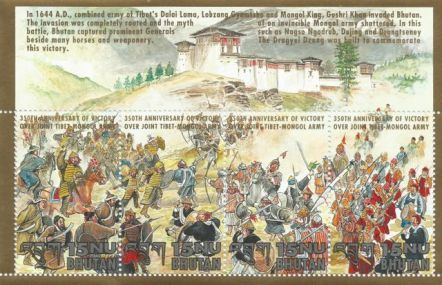

One more example. Everyone knows that Tibet invaded Bhutan in 1644. The Bhutanese repealed them and as a mark of victory Drukgyel Dzong was built. That’s it. However, the 1644 and 1648 military invasions were not as simple as that. They were meticulously planned, armed and launched by the Mongol warlord, Gushri Khan, who was a descendent of Genghis Khan. It was a formidable army of combined Tibetan-Mongol forces. And by the way, the Mongols, since the time of Genghis, had not lost a war and their empire once stretched from the Sea of Japan to western Europe. The 1648 mission was not just to capture Zhabdrung or to retrieve Ranjung Kharsapani but to occupy Bhutan – once and for all. In fact they entered in three different places – Paro, Punakha and Bumthang.

To cut the long story short, the Bhutanese forces led by Tenzin Drukdra launched a surprise attack in Paro, one night, and completely eliminated the invaders and captured their generals. The 1648 loss was perhaps one of the very few battles that the great Mongols ever lost in history. Tibet was also enjoying a period comparable to the times of the Yarlung dynasty.

But somehow we prevailed. Isn’t that music to our ears? Doesn’t this mean anything to you as Bhutanese? Wouldn’t you now look at Drugyel Dzong with a bigger pride?

By the way, the Treaty of Punakha was signed in 1910 and not in 1912. But I am sure you were really absorbed by the narratives here that you didn’t bother about that minute detail, right? That is the essence of learning history. The bigger picture is more important. I am not saying that you learn the facts wrong. What I mean is that one should internalise the meanings instead of memorising the numbers.

Our country’s prime resource is our people – to paraphrase His Majesty the King. What we learn, believe, have faith in or take pride for, will ultimately determine whether our country will reach for greater heights. And if the national pride is today missing or lacking, I would put the blame squarely on our inability to appreciate history. By “we” I include the society in general – and not just history teachers or curriculum designers.

As a result of history being taught badly no one takes interest in this subject these days. This is evident from the fact that it is never a part of our daily conversation or of any social gathering. There has not been one major conference or workshop on history as far as I can remember. We don’t even have a history Society that would serve as the authority on the subject.

As is life, so is a nation. It is only through knowing your past that you can cherish the present and move confidently into the future.

My prayers as we close the 109th National Day celebration is that we could resolve to take greater interest in our own history.

~~~~~~~~

As someone with a deep love of history, I enjoyed your passionate appeal to the reader that Bhutanese history be taught with renewed meaning and relevance. Your concerns about how history is taught in Bhutan are mirrored in classrooms in the United States. I have often wondered if history, for any citizen, is an acquired taste; something that grows on a person after years of living have left threads of personal stories woven across the landscape of a lifetime. My love of history has been fostered through oral history projects in which I read or listened to the recollections of elders; pioneers, homesteaders, war veterans, retirees, my own mother and grandmother. I recently visited Bhutan and ‘felt’ history every place I went. It oozed from the landscape, the architecture, the art, especially art in the temples, everywhere it seemed. How could it be that teaching history to students in a country where history permeates everything around them be difficult? Perhaps the development of an oral history program in which students engage their elders? Love of history starts with love of story. There are no better story sharers than the elderly; a grandparent, an auntie or uncle. Even if the story is from one small span of a lifetime, if the student engages in a process to learn about the past, their thirst for learning about the past will grow from that small act of listening. Teaching history is code for teaching stories. The way to teach stories is to teach listening.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kathleen,

Thank you for your kind words. I can understand what you mean that you see and ‘feel’ history in Bhutan.

Without being too nasty our people are bit like a fish that does not feel the water. We take too many things for granted.

Your suggestion for a oral history field work is great. I know my friend, Sumjay, did something similar in Sherubtse. I will ask him to take it further.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading your writing on how much is history important la sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your kind words, Kinzang

LikeLike

Great, because you lose your history, you lose your identity

LikeLike

Pingback: Teaching history. Talking history | Dorji Wangchuk