Identity has been mankind’s longest search. The question of “who am I?” has intrigued thinkers from Plato to Prince Siddhartha to Descartes. For us in Bhutan, this question has become even more relevant, as the country faces the onslaught of technology and outmigration, and the dilemma and divisions brought about by changing politics and policies. Simply put, what does it mean to be Bhutanese? This lack of common understanding, I believe, forms the core of our challenges – whether it is at an individual level or as a nation. Drawing from my PhD dissertation, I will attempt to give a definition to this slippery topic.

Identity has several definitions and concepts. Depending on the discipline, there are racial identity, gender identity, religious identity, cultural identity, political identity and so on. Here, by identity I am looking at the one coming from psychology – as in the personal identity, which describes one’s distinctive attributes that make a person unique. And more so, to the sociological definition, which refers to qualities, beliefs, and traits that characterise a person or a group. Scholars argue that it is the social circumstances in which people have been raised that determine the ways in which they identify themselves. Identity is, thus, believed to be produced through social interactions and experiences.

The traditional, virtual, and hybrid communities

A traditional community is where everything is shared – life, work, happiness, or sorrows. When you build your house, the whole village comes together without expecting a payment. Wherever celebrations and ceremonies are taking place, everyone is invited by default.

Nature and spiritualism occupy the centre stage in this community. It is not humans, but nature, which dictates everything including the pace and rhythm of life. Places are not just physical spots. They are sources of stories and spirituality, and of inspirations and wisdoms. Thus, kinship and family ties are extended not only to humans, but also to nature and to nonhuman forces and spirits. For instance, tigers are referred to as azha tah (maternal uncle Tiger), bears as aku Dhom (paternal uncle Bear), and elephants as memay Sangye (Grandpa Buddha). Certain deities and mountains are also embraced like a family. Examples of case in point are ama Jomo (mother Jomo), memay Chador (grandpa Vajrapani), or as memay Ralang – a mountain in Trashigang. Kinship terms do not only serve a referential purpose. They build and sustain emotional connections too. This may be the reason why Bhutanese are close to nature and mountains.

Time, in a traditional Bhutanese community, is conceived as cyclical and not as linear. For instance, older people do not remember their age. They will remember their Buddhist zodiac signs, which is a cycle of twelve years known as lo-kor. The correct question to ask is, “How many cycles have you done?” instead of, “How old are you?”. Nature also defines the flow of time. To lift from American sociologist Robert Levine, traditional Bhutanese prefer event time, and not clock-time. In rural Bhutan, you don’t say, “I will see you at 9.30”. Rather it would be something like, “Let’s meet before the Sun sets, and after we collect our cows from the jungle”. This may explain why Bhutanese are rarely on time.

At the other extreme of a traditional society is the virtual community where humans, instead of nature, are at the centre of the universe. Here everything must be rational, logical, scientific, and black and white. It is also where time is linear. The resulting characteristics are: more individualism, expressiveness, innovation and celebration of anonymity. Money and materialism are means to enhance one’s self-worth or belonging.

Striding between tradition and technology, between collectivism and individualism, and between money and meaning, is the hybrid community. Time starts to become linear here, and the cyclical concept is still accepted. Nature has its place, and so does rational science. There is more “we” and less “me” in this group, and wealth is to enable one’s pursuit of the greater good.

Therefore, the traditional Bhutanese identity is an interdependent self, which consists of a personal self, social self and a spiritual self. The social self is derived from one’s social identity as a parent, and from the vocation one practises. The spiritual self is the recognition and internalisation of the external nonhuman energies and spirits.

The chronotopic Bhutanese identity

While one may observe these identities manifesting in different generations or communities, an interesting finding is that you can also notice these multiple identities in individuals, as one lives through the changing circumstances and contexts in life. The ingredients of the interdependent self – the personal, social and the spiritual selves, are all there in each one of us – in different dosages and degrees. I call this the chronotropic Bhutanese identity. Chronotope comes from Greek and it means time-space (chronos means time, and topos – place). The term was coined by a twentieth century Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin as a literary tool to posit the idea that time and place are inseparable in art. Chronotropic identity basically argues that a change in timespace configurations triggers a seamless shift in roles, behaviours, discourses, modes of conduct, mindsets, and cultural practices.

Take for example, the people of my generation – the predominantly hybrid group that grew up in a traditional setting, and got introduced to science and technology. We start the day by reciting a few lines of prayers. We then get up, wash and offer water and incense to the altar, have breakfast and open a laptop at work. The virtual community, on the other hand, may be on the technology from the moment they wake up till they retire to bed. They would attend spiritual calls on special religious occasions, or visit a temple like Dechenphu if they need something. Conversely, the traditional people access the technology too but not as a default mode. It sees materiality both in technology and spirituality, though.

The key to a harmonious Bhutan, then, is not only to recognise these parallel matrices, but, to paraphrase another philosopher, Jean Gebser, to embrace an integral consciousness that would involve a more holistic understanding of the reality, which includes both the rational thoughts and the intuitive sense of interconnectedness and spirituality. The Generation Z (or Gen Z – referring to people born roughly after 1999) must not refute the traditional as archaic and outdated. On the other hand, the hybrids should not discard the Gen Zs as not adhering to established norms. There is space for everyone.

What’s going on in Bhutan, instead

From a sociological perspective I feel that there is a loss of innocence among traditional Bhutan, which was accelerated by political changes.

By ‘innocence’, I mean where people are honest, spontaneous, sincere, always helpful, and trusting of others, and have a strong moral compass. In general, people who haven’t been corrupted by the evils of modern society. You can find some in rural Bhutan.

The loss of innocence has led us to empathy deficit among the hybrids – because of newfound power, ego and fear. And then, among the younger generation, a decline in the sense of belonging from being not understood. Unless we address these, people will go off on tangents in search of meanings to life, instead of drawing satisfaction and purpose from the service to the collective.

My greater concern, however, is for the next generation. For better or for worse, from an interdependent-self that we should be, Gen Zs are growing up as more expressive, questioning and independent selves. Instead of love and guidance by the collectivist society, it is viewed as a social divergence. Our youth, then, feel misunderstood, and even rejected. Research shows that when they are isolated from their physical communities, they will either go away, shut off completely, or hide behind computer screens and smartphones and try connecting with the online world. One issue with living on social media is the abundance of information and knowledge there – both good and bad. Information is not knowledge, and knowledge is not wisdom. In life you need wisdom. You develop wisdom only when you engage with the physical world, where you roll out your sleeves and get your hands dirty. This may explain the success of the Desuung program. It gives that opportunity – to go hands-on and feel a sense of belonging to a meaningful community.

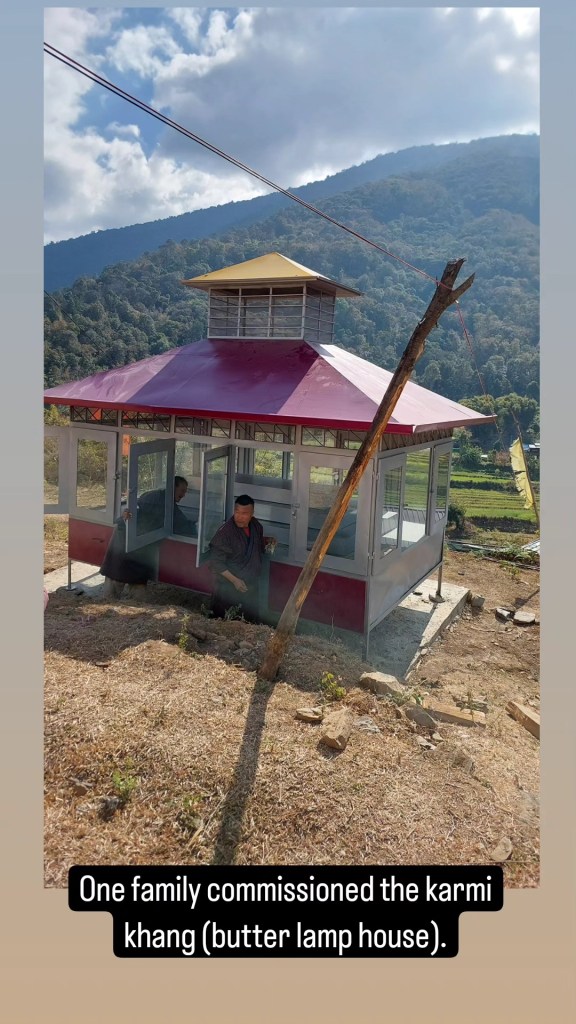

Fortunately, some compassion is still around in Bhutan, which is evidenced by frequent and successful fundraisers on social media, like for someone in Australia who needs a surgery, or for a fellow Bhutanese who has to go for a transplant in India – or to simply save some yaks – or build a stupa.

So, what does it mean to be Bhutanese?

To be Bhutanese means to be compassionate, altruistic and spiritual; and be aware of one’s place in a family, community and country; and share this temporary space with other beings – that are both seen and unseen. If Bhutanese, young and old, could embrace this more, instead of over stressing on cultural paraphernalia or purely pursuing economic dreams or power, a brighter and a fulfilling future – as individuals and as a nation, will be more than guaranteed.