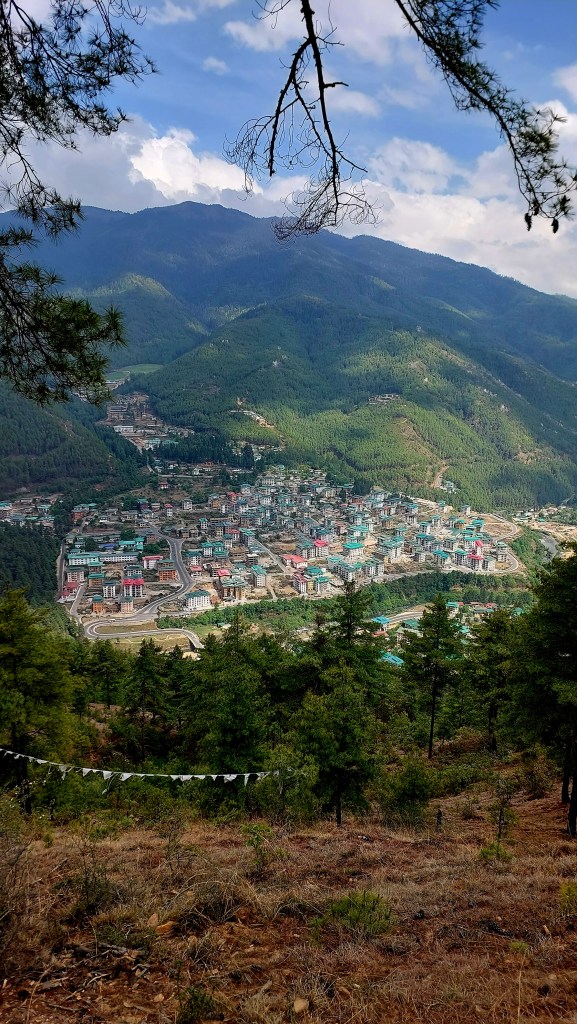

These days my morning walk consists of thirteen or 25 rounds of this temple in Zilukha in Thimphu. It is 10 minutes from my place. For those of you in Thimphu who may not be able to hike up to sacred places like Phajoding or Dodeydra, for whatever reasons (including laziness), you have Zilukha temple in the city that is as sacred, and where you can visit without too much formalities.

The temple is the heart of the Thangtong Dewachen Nunnery. It was built in 1983 by drubthob Rikhey Jadrel Rimpoche (1901-1984), who was considered as the 16th reincarnation of drubthob Thangtong Gyalpo (1361-1485). In fact Rikhey Jadrel was also known as Memay Drubthob.

The central statue of the temple is Thangtong Gyalpo (1361-1485) – one of the greatest yogis, and a master builder and artiste in Vajrayana Buddhism. To its left is an mesmerisingly beautiful statue of Drol-kar (White Tara), and to the right is Neten Yenla Jung (Angiraja) – one of the Sixteen Arhats. All the clay statues were created by the best jinzob (mud-artist) of our time, Lopen Omtong from Trashigang Bidung. The consecration ceremony of the temple was presided by His Holiness Kalu Rimpoche (1905-1989).

Guru Rimpoche’s vajra

It is believed that inside the Thangtong statue is a sacred dorje (Vajra) buried there, which apparently belonged to Guru Padmasambhava himself. The construction was started in 1981 and all the nang-zung (inner relics) for the statues were granted by Lama Sonam Zangpo (1888-1982), who was also supervising the statue construction. As the yeshey sempa (the most sacred relic) Lama Sonam Zangpo requested Memay Drubthob to put the Guru’s dorje, which the Drubthob was in possession of. Memay Drubthob refused at first, but when Lama Sonam Zangpo threatened to walk away, he relented, according to a reliable source. Lama Sonam Zangpo is supposed to have told that they were all getting old and didn’t have many years to live and that no one knows where the sacred dorje would end up if it is not placed there for the benefit of all sentient beings.

According to another source, around the same time, Memay Drubthob invited the indomitable Jadrel Sangye Dorje (1913-2015), popularly known as Jadrel Rimpoche, to the consecration ceremonies. Jadrel Rimpoche unapologetically replied that he would come only if the Guru’s dorje was offered and buried in the main statue as the principal yeshey sempa.

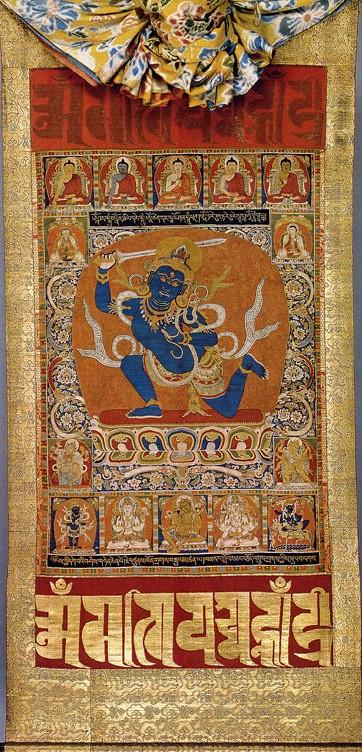

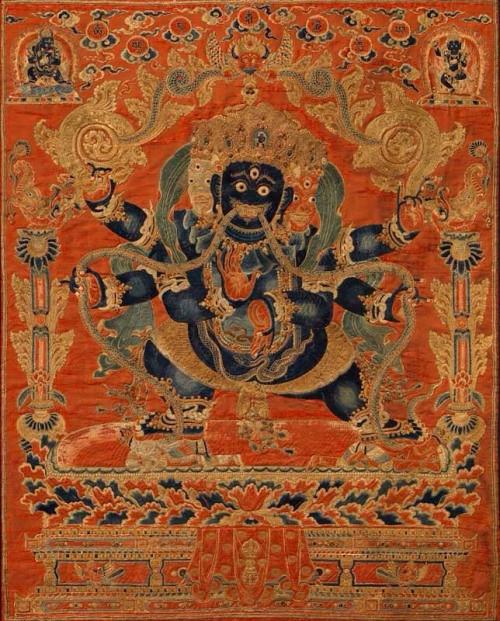

The dorje is believed to be the one that Guru Padmasambhava had used to tame the demons as shown in sampa lhendrup iconography. Hence while the temple may be relatively new, the inner relics offered by Lama Sonam Zangpo and the Guru’s dorje and the presence of all the great yogis such as Kalu Rimpoche and Jadrel Rimpoche make this temple a very special place. It is believed that any wish you make at Zilukha temple would be fulfilled. It is considered to be particularly powerful to clear one’s obstacles, and negative forces directed towards you, thanks to the Guru’s powerful dorje.

Why visit this temple?

We visit many sacred places and monuments purely based on legends we hear and believe. This temple in our city is not only convenient but it was built during our time by the greatest yogis and masters of the century – Rikhey Jadrel Rimpoche, Lama Sonam Zangpo, Kalu Rimpoche and Jadrel Sangye Dorje Rimpoche. Simply put, the temple is an established fact.

May Guru Padmasambhava hear your prayers and moelam

More on Thangtong Gyalpo

1. Thangtong Gyalpo is believed to be the mind emanation (thug-truel) of Guru Padmasambhava. It is believed that Guru considered revering Thangtong as revering him.

2. Thangtong Gyalpo, whose real name is Tsundru Zangpo, was an engineer, artiste, yogi, and an adept. He is considered to be the deity of people who take up professions such as engineer and art.

3. The world’s first opera was not Italian but Tibetan. It is called Achey Lhamo, and it was authored by Thangtong Gyalpo. Today Achey Lhamo opens all major Tibetan functions and festivals.

4. Thangtong Gyalpo means King of the Empty Plain. While he was meditating in the Gyede Plain in Tsang, five dakinis appeared to him and sang verses of praise: “On the great spreading plain; The yogin who understands emptiness; Sits like a fearless king; Thus we name him King of the Empty Plain.“

Supporting the temple:

The temple is independently managed and sustained. And so there are less formalities for visiting it. And the generous offerings of the devotees for prayers and rituals help to maintain this amazing gem in our city.

I often make requests to the nuns to recite barchel lamsel (obstacle-removing) and sampa lhendrup (wish-fulfilling) and make some offerings.