In social anthropology, kinship address system is how members of a family refer to other members of the same family or a clan. For example, we call our mother, ai, in Dzongkha and ama in Tshangla-lo of Bhutan, and apa for father in both.

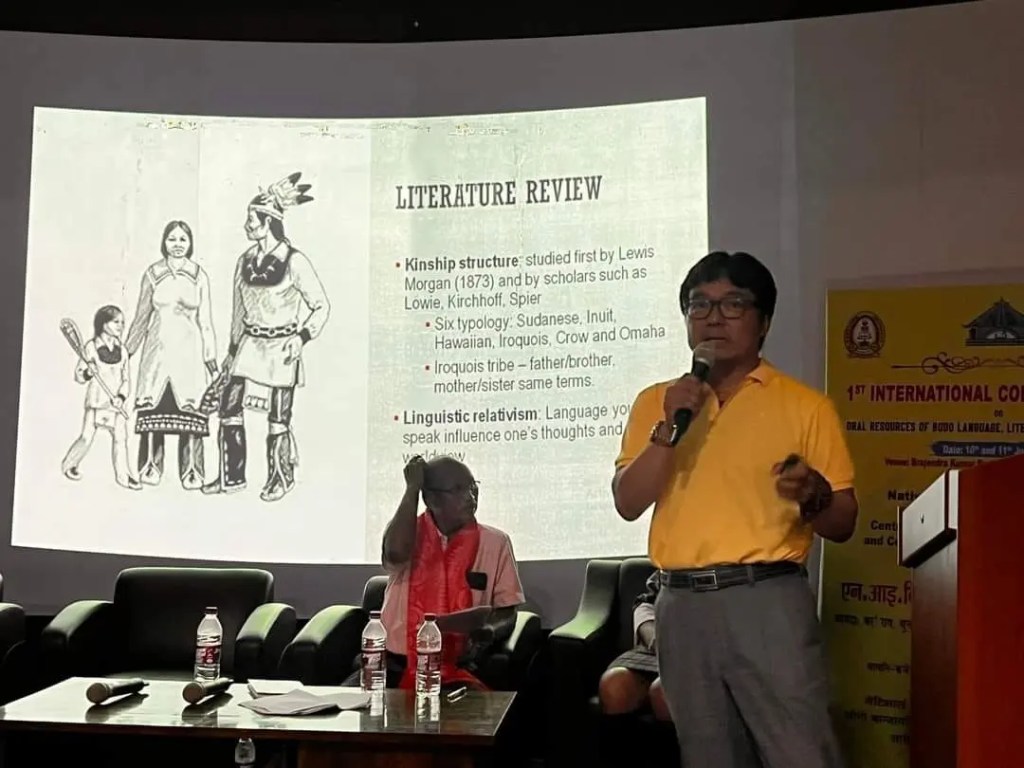

Different communities, ethnic groups and cultures around the world have different kinship address systems. For instance, among some native American nations like the Iroquois, paternal uncles and father are addressed with the same term, while mother and aunts had the same. In some other cultural groups, they have gender neutral terms for brothers and sisters.

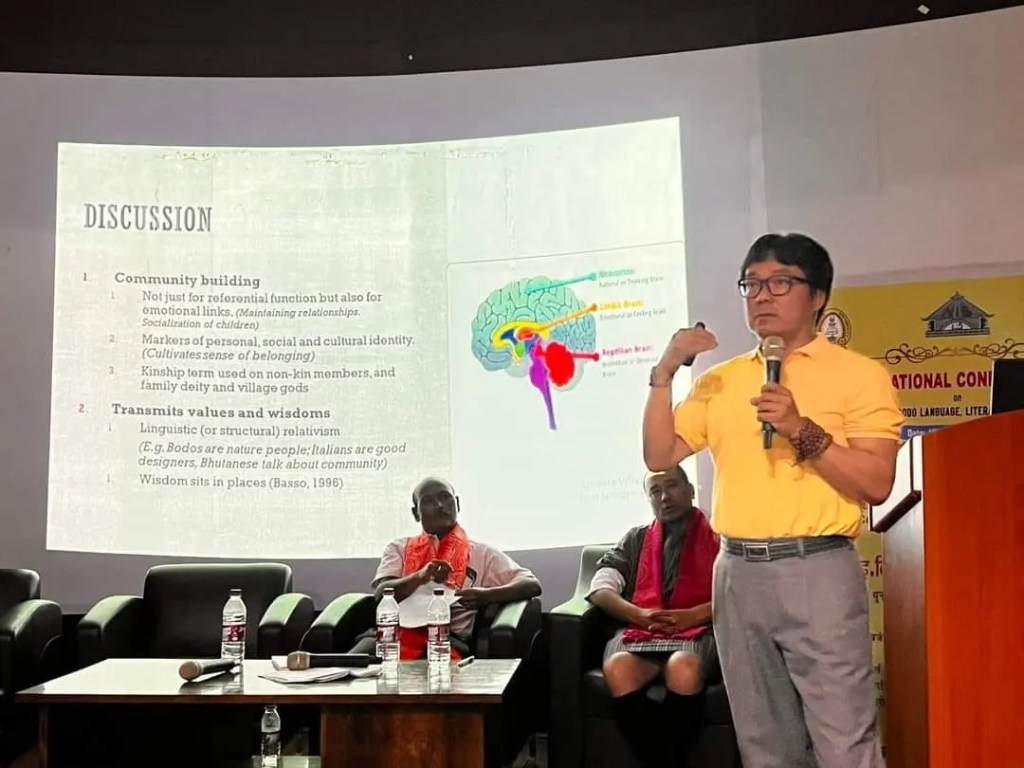

The study of these terminologies reveal a lot about the value systems, what is being valued, and the social and cultural traditions. Besides, native languages have been passed down from earlier generations bundled with stories, beliefs, heritage, wisdom, and memories.

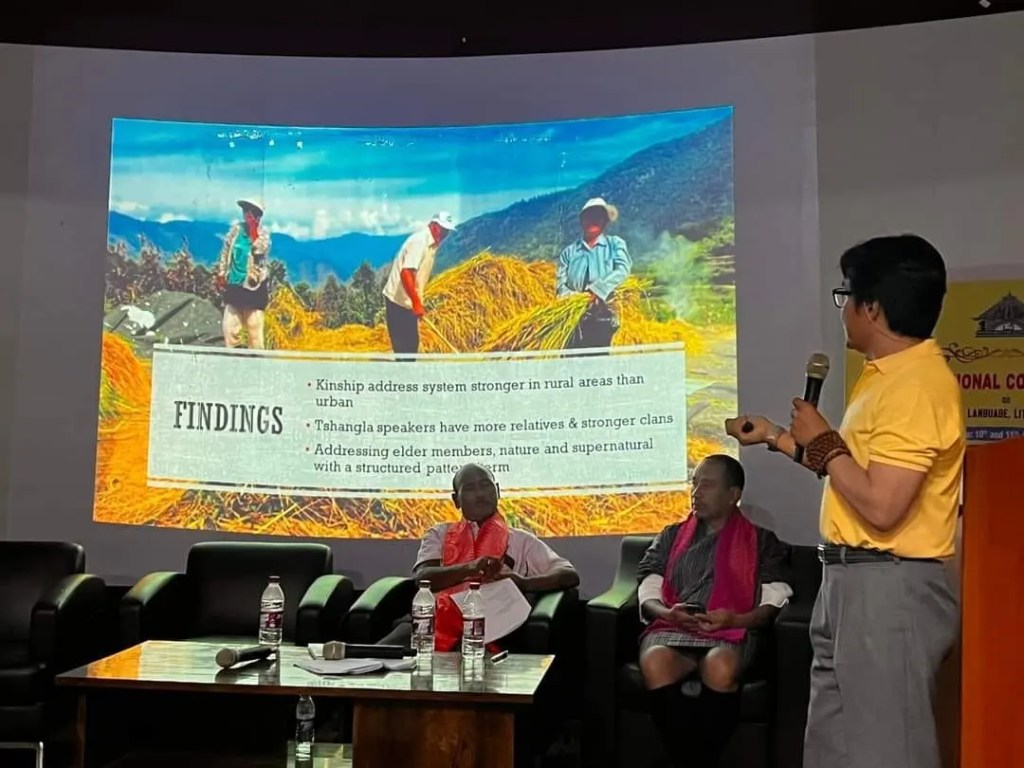

The Tshangla community of eastern Bhutan has some of the world’s largest repertoire of kinship terms – around 30 in all. English has around one third – around 10. This suggests that such rich terminologies help build and sustain the large extended family culture among the Tshanglas. Having a term for each member, such as aku (father’s younger brother), apchi (father’s elder brother), ajang (mother’s brother), azem (mother’s younger sister), amchi (mother’s elder sister), may help establish an emotional link between interlocutors, and not just serve the referential function. Consequently, people feel connected to every member of the family or community.

Kinship terminologies also find their way in the socialisation of young children. Tshangla elders make every effort to teach the children the proper kinship term, and how people are related to each other. For instance it would be something like, “She is not amchi. She is your ani. She is father’s mother’s sister’s daughter”. Such a structured socialisation process makes everyone feel part of the community. It then creates a strong sense of belonging in the people. Eventually a stronger community, and a nation is achieved.

Standby parents culture

The words, amchi and azem (mother’s elder sister and younger sister respectively) are abbreviated from ama-chilu (big mother, mother’s elder sister) and ama-zemu (small mother – mother’s younger sister). These term imply that in the event of the demise of the biological mother, the sisters of the mother have the responsibility to fill in and take the child/children as their own. Likewise aku and apchi are abbreviated from apa-zemu (small father, father’s younger brother) and apa-chilu (big father, father’s elder brother). This arrangement was necessary in the past when maternal mortality from child births were very common. And men left for trade, or into the jungles, and sometimes did not return.

This tradition also entailed that you could not marry your parallel cousins, while cross cousins was allowed. The standby-parents culture could entail your parallel cousins becoming your siblings at any time. In fact the kinship terms for parallel cousins are the same as sibling terms – kota (younger brother), usa (younger sister), ana (elder sister), ata (elder brother).

Not just cosanguineal

Traditional Tshangla society requires one to acknowledge relatives up to seventh degree. This even include affinal relatives such as through marriage, besides the consanguineal relatives, which are relatives through bloodline. A cousin of mine followed this rule and estimated that I have 2,400 relatives.

Tshangla elders also insist on reconnecting with affinial relatives of the past, arguing that we are sognu thur (one family). For instance, there were inter-marriages between my ancestral house in Tashigang and the house of Ngatshang Koche. This past alliance entitles us to refer to members and descendants from that house as our relatives – as one family.

(Excerpt from my paper – Kinship terminologies in Tshangla-lo – a rhetorical device for community building amd sustenance, delivered at Central Institute of Technology, Kokrajhar)

The PPT file can be downloaded from the link below

I offer my sincere congratulations to you, Dr., for your exceptional work. Your remarkable achievements have truly impressed me. If I may, I kindly request your assistance in obtaining the 30 terms you have discovered during your research. I am deeply interested in this topic, as I am currently a student pursuing an honors degree at the College of Language and Culture Studies. Our curriculum includes a module on research, and I have recently conducted my own study focusing on a specific community. Coincidentally, my research explores the significance of Tsangla kinship terminology in shaping the Nyewa Thungma culture within the Tsangla community. Today, I had the opportunity to defend my research as part of my academic journey. However, my desire to delve further into this subject remains strong, particularly through a comparative study of the kinship terms used in the Kengkhar community, situated in the Mongar Dzongkhag, in relation to other Tsangla communities. Therefore, it would be immensely appreciated if you could kindly provide the aforementioned 30 Sharchop terms.

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can download the ppt. The full typology is there

LikeLike